The Plot Against Climate Tech

Should a climate tech founder take oil company money? It depends.

Welcome back to Wicked Problems. The climate tech newsletter that some people are saying if you listen to it backwards at 1.75x speed will reveal the exit package of Bernard Looney from BP.

We’re not big on conspiracy theories. Ironically it’s a lot scarier to realise that the world runs more on cockup and people making it up as they go than to think there’s a sinister cabal manipulating events.

But of course, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t any. It’s just usually that when a real conspiracy does come to light, as Deep Throat told Bob Woodward in All the President’s Men, “The truth is, these are not very bright guys, and things got out of hand.”

Then again, the oil industry might be a different case. We’ll get to that in a minute.

Should you take oil money?

It’s a question people have been asking since the invasion of Ukraine suddenly replenished the industry’s coffers. See this Sifted piece from a year ago. As Freya Pratty reports, some founders “wouldn’t touch Big Oil money with a barge pole” on principle. Others, often those who’ve taken oil funding, take the opposite view:

Others in the climate tech industry take the opposite view. Kristina Hagström Ilievska from Baseload Capital — a Stockholm-based firm that funds the deployment of geothermal energy power plants around the world — is one of them. Baseload is 7% owned by Chevron.

“It was obvious for us to turn to Chevron because they, and the oil and gas industry more widely, have intellectual property that is very important for the geothermal industry,” Hagström Ilievska says.

Drilling into the Earth’s crust is the most technical and costly part of geothermal deployment — a task oil and gas companies have been doing for a long time.

For Hagström Ilievska, it’s fine for any founder to accept money from oil and gas, even if they’re not working in an area where oil and gas expertise is useful.

“If everybody takes part in the transition, it's going to be much faster. If we leave someone out of it, it's just going to be a fight that takes longer,” she says. The criticism of the oil and gas industry is correct, she adds, but the answer is to help them transition and to encourage them to put money into green tech.

This piece ran before the hard pivots earlier this year of Shell, BP and others to double down on oil and gas investment.

Funders tend to take a more nuanced approach. There is Big Oil and then there’s Big Oil, looking a lot like Daniel Day Lewis creepily twirling a moustache in There Will Be Blood. Not all oil companies (or oilfield services or engineering firms) are the same. Some managements have a better grasp than others on managing portfolio risk to bridge the energy transition.

Confirmation Bias and Execution Risk

There was a great discussion on this issue on The Energy Gang, the Wood Mackenzie podcast, a couple of weeks ago. And it led to a bombshell I’d missed on first listening.

Amy Myers-Jaffe, of NYU’s Energy, Climate Justice and Sustainability Lab, was responding to host Ed Crooks’ question on whether the question marks over Big Oil’s commitment to the transition is going to slow things down. Here’s what she said:

So one of the things that bothers me about this whole questions of how fast we can go in the transition, is you’ve got these sort of false distinctions. You know, you got a big, giant, integrated energy company, saying they can make 17 or 20% rate of return on an oil and gas project. So they just can’t accept, y’know, a 7 or 10% return on a renewable energy project.

When in the end those oil and gas projects have never actually achieved those IRR numbers. So it’s just a bias. If you can really manage execution risk…whether it’s from an oil field or an offshore wind farm or utility scale solar and battery installation, it’s about execution…

It’s really about people and having the best management teams and implementers in this space.

She went on to talk about whether it’s good or bad that the oil industry is investing in oil again.

“What I want to know when I’m looking at a company, your strategy cannot be that you’re investing and hoping for a war. Right? …Exxon made money last year because Russia had a war with Ukraine. That’s not a business strategy. That’s just a lucky year.”

Here’s that clip:

Jaffe then went on to drop something as fact that many had long worried about in their most paranoid moments. What if someone was actively trying to “thwart” innovation in climate tech?

Here’s what she said:

The 1% Conspiracy

I mean, [Big Oil] are the companies that have the capital right now. And, you know, two thirds of climate tech startups are are winding up with some of that capital. And so really the Devil’s in the details.

And I won't name names, but there's one company out there, that's a big oil company, that tries to take 1% of some, all these different startup companies, and then they want you to sign that you can't bring in any new investors unless that company gives permission.

And it's like, it's like honestly, their strategy sounds evil. It's kind of like, let's see how many startups we can thwart by taking a 1% share.

I was talking to someone from the VC community, and they're like, we don't even call them anymore because we just don't want to deal with you know, their sort of deal killer mentality.

So it varies from company to company, you know, which of the companies are serious and who has the strategy and who, who doesn't.

Listen for yourself:

Keep in mind that Jaffe isn’t some granola-crunching Just Stop Oil protestor. She’s one of the most respected commentators of the energy sector. She regularly has bylines in the, erm, not particularly woke Wall Street Journal. Most recently, throwing cold water on the chances for rapid electrification - as both being unfeasible and actually undesirable, in her analysis.

So we’re not talking about a source who casually throws conspiracies into the ether.

Whodunnit?

We do love a mystery. You’re probably wondering which supermajor is out there with this predatory investing/predatory delay strategy. We do have our suspicions, and indeed heard a journalist ask a leading question to an exec probing the motives for their investments in climate tech startups, on the fringe of a conference earlier this year.

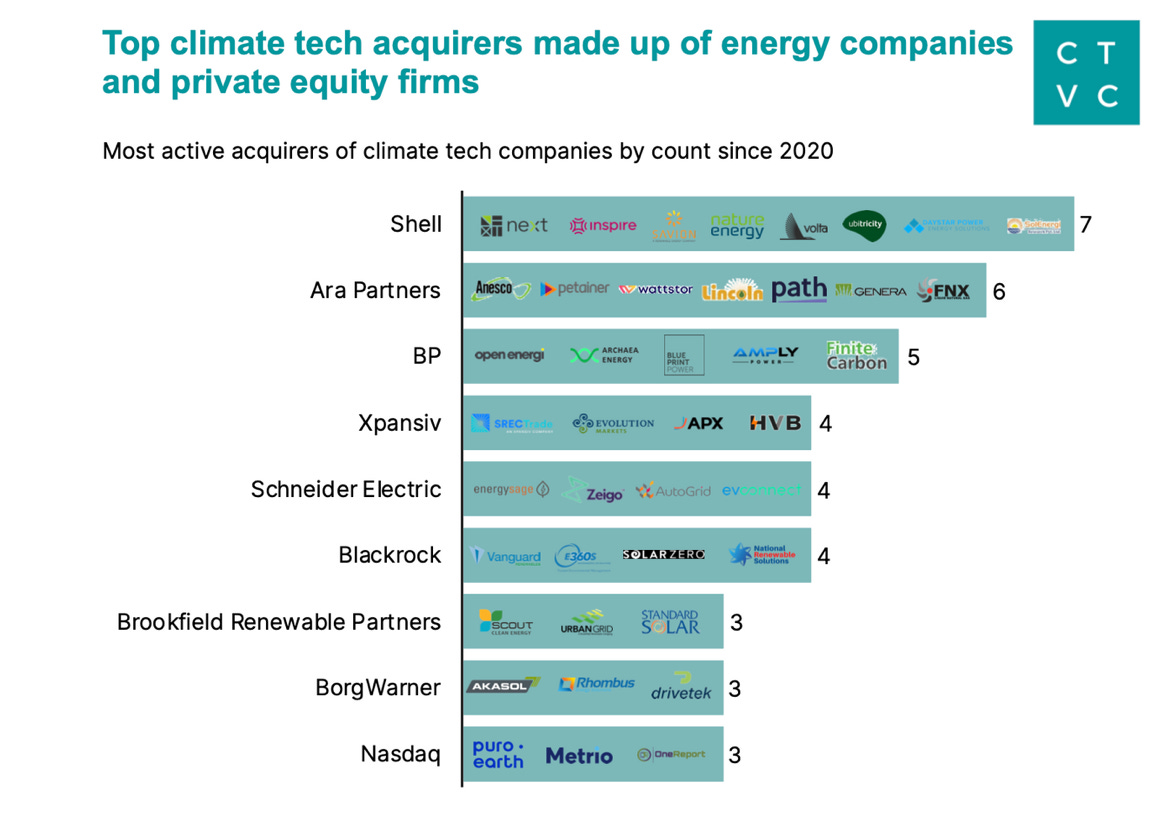

CTVC laid out the biggest exit routes/acquirers earlier this year in a nifty graphic:

Which might give a sense of who to rule out. We’ll keep our ears open. Do hit me up at info@wickedproblems.uk with your own guesses.

Meanwhile, let’s be careful out there with those term sheets, people.

Pursued by a Bear

OK we can’t actually confirm it was a bear that chased Bernard Looney out of the CEO office at BP. While the FT had the scoop, Laura Hurst at Bloomberg has some of the best analysis of the potential impacts on BP’s low-carbon investment strategy for the energy transition. Spoiler alert. It’s not good news:

From the North Sea to West Texas, Looney pushed BP into greener territory, with big bets on hydrogen and offshore wind. Without the architect of that pivot, the company’s direction is now in question.

The change at the top of BP is “definitely a big surprise,” Edward Jones analyst Faisal Hersi said in an interview. A change of strategy back to more fossil fuels “would be positive. The pace of BP’s energy transition was just too ambitious.”

In 2020, just a week into the top job, Looney announced BP would embark on an ambitious net zero path to help fight climate change. It was a bold shift, not only because the company was at the time considered a climate laggard, but also because Browne’s previous attempt to re-brand BP as “Beyond Petroleum” in the early 2000s ended mostly in writedowns.

Investors were lukewarm over Looney’s approach.

UPDATE: FT’s Lex column weighs in to warn BP against slowing their transition, ignoring the advice of the Faisal Hersis of the world :

This has been no easy effort. The International Energy Agency may expect demand for fossil fuels to peak before 2030. But the market has not rewarded BP for its efforts to invest in cleaner fuels. After an enthusiastic start to his tenure in February 2020, when he set out net zero plans, BP’s share price performance of 14.5 per cent including dividends has trailed that of its largest peers.

Early this year, Looney appeared to shift away from his environmental commitments. Plans to scale back oil and gas production cuts by 2030 went down badly with climate activists. Yet BP needed to achieve better investment returns from its spending on cleaner technologies. Investments in transition fuels such as biogas — BP bought Archaea for a hefty $4.1bn in December — offer higher returns than headline grabbing wind farm projects.

Thoughts will now turn to succession. Note that BP’s board had fully backed Looney’s strategy. His charisma smoothed its shift to cleaner technologies — even if it will remain 75 per cent fossil fuel dependent at the decade’s end. Someone equally politically agile is required to execute this plan. Transition investments will provide a quarter of BP earnings by 2030, according to Citi.

Time will tell, but the loss of a leader of one of the supermajors who was “too ambitious” in trying to accelerate the transition is probably not great news. Stay tuned.

Thanks

If you’ve read this far, you hopefully found something worth your time. We’re glad you’re here. Why not share it with some friends?

Are we doing this too much? Not enough? Think we’re leaving something out? Drop us a line at info@wickedproblems.uk to send us story tips, bribes, or abuse.