At the close of 2024, New York followed Vermont and became the second jurisdiction in the world to try and force carbon polluters to pay for things necessary to adapt to the increasing effects of climate change. Like better drainage systems, more heat-resilient infrastructure like bridges, roads, hospitals and schools. Or perhaps - in what would be a wildly popular move according to polling from Data for Progress - requiring oil and gas emitters to pay for carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Like Vermont, New York’s law is deliberately crafted to draw from the “polluter pays” principle at the centre of the “Superfund” - aka the less catchy Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). In it, the US simply ordered the chemical industry to help pay to clean up toxic waste sites via CERCLA without having to take them to court. And in a solemn coincidence, signing Superfund into law was one of the last official acts of President Jimmy Carter, who passed away just three days after NY Gov Kathy Hochul signed Climate Superfund into law 44 years later.

To be sure, there were challenges to its constitutionality over the years because it compels payment for past acts that were not illegal (and in some cases encouraged by government policy). And the current US federal judiciary doesn’t seem as interested in precedent as it was 40 years ago. But it did survive, which gives hope to those planning to defend the laws in court. Just this week the expected counter-attack against Vermont’s law began with the US Chamber of Commerce and the American Petroleum Institute arguing that no one state has the authority to penalise companies for acts outside of that state’s boundaries.

When we first spoke to journalist Dana Drugmand in the first part of 2024, Vermont was just getting ready to take the plunge. Today she’s back to talk about New York’s move, as well as her picks for 10 big moments in climate litigation and legislation last year.

As the US once again turns its back on climate responsibilities at national level - with moves to even prevent the effective collection of climate research - these legal moves by cities, states, international courts, and countries other than the US, stand out even more as bright spots in the gathering gloom.

It’s as if a bunch of litigants and courts around the world just decided that the “carrot” approach best represented by the UNFCCC COP process and Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act were, to put it mildly, not getting it done1. We called it the Season of the Sticks:

2024 was a bumper year for legal actions on climate - whether holding governments or polluters to account for acts of omission as well as acts of commission. Just a few highlights:

The Klimaseniorinnen case at the European Court of Human Rights ruling that governments can be held liable for knowingly failing to protect their citizens’ right to life, threatened by the effects of climate change.

Courts in Montana, not typically considered a bastion of squishy left/liberal ideas (Trump won the state by more than 16 points), ruled in favour of people at the younger end of the spectrum - upholding the right to a healthful environment enshrined in Montana’s state constitution and the claim that state government was required to do more to limit emissions. Crucially, courts rejected the idea that simply because Montana represents a small percentage of global emissions that absolves the state from its responsibilities.

Here in the UK, the Supreme Court ruled in Finch v Surrey County Council that the council acted unlawfully in giving permission to try and extract oil from a site near Gatwick Airport at Horse Hill - because it failed to take into account how the 10 million tons of “Scope 3” emissions from burning that oil would affect the climate. With big implications for future projects like planned further North Sea gas and oil wells.

California and Vermont, amongst other jurisdictions, filed suit against oil majors alleging that because marketing of their products deceptively misled consumers about the effects those products were having on the climate, the profits gained from that deceptive behaviour was unlawful and therefore. Both survived initial legal counterattack from the oil and gas industry and other polluters. California AG Rob Bonta successfully kept the case in state court, and Vermont successfully fought a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

And the International Court of Justice (aka The World Court) held dramatic, groundbreaking hearings in which countries - especially those already seeing their lives and livelihoods suffer from repeated extreme storms, rising sea levels, extreme heat, wildfires, and more - argued that international law doesn’t simply allow polluting countries to wilfully harm other countries through climate damage. And as Vanuatu’s Ralph Regenvanu and others argued, the Paris Agreement is not a “get out of jail free” card for polluters. The ICJ advisory opinion on what obligations national governments have to do something about climate may come as soon as late spring of this year.

And those are just a few.

Pincer Movement to Make them Pay

Different cultures will have differing views on what justice means. If the cycle of elections during 2024 demonstrated anything, it’s that anger at perceived unfairness might not be the most noble of human emotions but it is probably the most basic and most politically powerful. That’s why the combination of climate lawsuits and “polluter pays” laws like those now on the books in New York and Vermont is potentially so potent.

You don’t need a PhD in atmospheric chemistry to get the argument:

Big Oil has known for more than 50 years that their products were going to do this to the world. They spent billions of dollars - a tiny fraction of their profits - to mislead people about what their own scientists told them in the 1970s and to prevent action to stop them. And now the process of stopping emissions and living with the damage is going to be incredibly expensive. So f*ck them and take their money.

Winning arguments don’t need to be high-minded or sing kumbayah. Sometimes “payback is a bitch” is just more effective. Imagine a “pincer movement” in multiple guises on multiple flanks at the same time using that basic argument: a finely-worded legal brief in a human rights case; Superfund legislative language; a barn-burning speech from AOC; and a Climate Majority Project organiser connecting the expense of flood defences to the reasons they’re needed…that starts to feel like harnessing how people actually feel and turning into a deep theory of change.

Going into 2025, there’s reason to think there are potential gains to be had there in making the case for climate solutions as not nice-to-haves, but must-haves with the moral punch of making the people who ought to pay to actually do it.

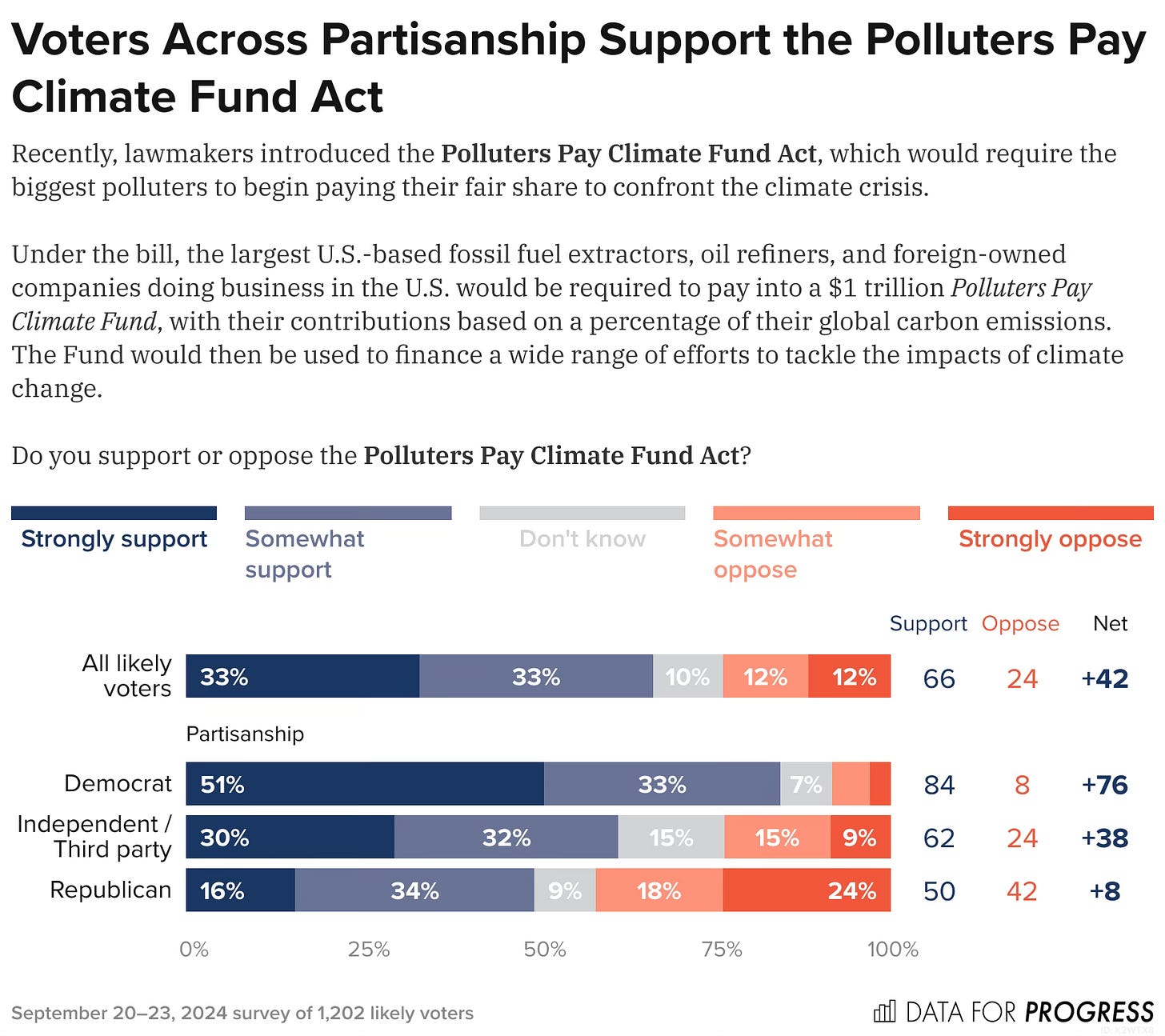

Encouraged by the Vermont and New York laws, there was an effort last year in the US Congress to follow their lead and pass similar legislation. When Data for Progress polled on the idea, they found it to be wildly popular:

Sponsors of a similar bill in California put it on pause after successful lobbying from the oil industry put progress in doubt. But the world’s seventh largest economy seems likely to be monitoring closely how the first two states fare in defending their law in court. The state’s attorney general Rob Bonta had a pretty nuanced view on how litigation like his and laws like those in New York and Vermont go together. In October he told Politico:

How does this relate to SB 1497, Sen. Caroline Menjivar’s Polluters Pay Climate Cost Recovery Act that would bill oil companies for past emissions to pay for climate damages? Do we need both?

We haven’t taken a position on the bill, but not at all surprised that there’s a desire in the policymaking space, by legislators in that space and separate from us, to seek remedies and pursue relief that they think is appropriate. This is how our democracy works. Different leaders elected to do their jobs think about the authority that they have, the jurisdiction that they own, and the action that they can take to solve a problem that affects their constituents. Sen. Menjivar is doing that in her way, I’m doing it in my way.

What Kamala and COP Have in Common

If there’s a lesson to be drawn from the popularity of these moves to hold polluters to account, and the failure (UK being a notable exception for unrelated reasons) of climate-policy-friendly governments at the ballot last year have in common, it might be this:

A politics that instinctively defends the status quo and flawed institutions that sprang from it and necessarily help to maintain it is a losing formula in the middle half of the 21st Century we just began.

I’m far from the first person to come to this observation when it comes to the future of US politics, and it’s particularly popular amongst the American podigarchy stretching from Know Your Enemy to Ezra Klein to Pod Save America to Tim Miller and Jonathan V. Last of the The Bulwark.

Where I think that insight translates to climate and climate tech is that sitting back, resting on laurels of perceived progress, playing it safe, convincing yourself that people with massive financial incentives to throw sand in your eyes can be persuaded to play nice (or at least fight fair), genuflecting to empty pieties, and hoping for the best — hasn’t worked out too great.

What does that mean for those working on climate and climate tech? It may mean recognising - without having to openly endorse, but quietly finding ways to create space for - the sorts of politics that between 2017 and 2020 created the space for policies that created business opportunities. But without the comforting fiction that everyone agrees “we [eg oil companies and small island developing states] are all in this together” or that turkeys will vote for Christmas.

The future can be better, faster, cleaner, cheaper. But there is a small but powerful minority who over 50 years have proven they will stop at nothing to prevent it from happening. So therefore we need to call out those people, work together to beat them, and clear the way for a future that benefits more than a few entrenched incumbent rentiers.

2025 Hopes and Fears

If you haven’t yet listened, big recommendation to check out Laurent Segalen, Gerard Reid, and friend-of-the-show Michael Barnard offer their 2025 predictions on Redefining Energy. Among the spicier (which make sense to me) takes: offshore wind in the US is dead for the rest of this decade; BP will be the first oil major to succumb when oil prices fall and be consolidated out of existence; and in 2025 700 GW of solar, 100 GW of battery storage, and 20 million EVs rolling off the line.

Second must-listen is Akshat Rathi’s conversation with Kim Stanley Robinson for Bloomberg’s Zero pod. As a huge fan of both men, it was a treat to listen in on a chat between two of the smartest people I know.

For a palate-cleanser, I’d highly recommend this (checks notes) essay in UnHerd by Yanis Varoufakis on why the Left needs to watch Star Trek and take it seriously - in particular its rejection of blind neoliberal techno-optimism and of authoritarian collectivism (and with that I assume degrowth, but we’ve asked him on the show to explain). Which is not a sentence I never imagined I would write.

Listen Up

We like to play around with outro tracks. The best we’ve heard so far is “well that’s….eclectic”. We’ll take it.

COP29 demonstrated that states couldn’t be counted on to keep their promises made even just a year earlier at COP28. And the result of the US election demonstrated that voters are more persuaded by loss aversion (but muh egg prices) than potential gain (mmmm…Green Jobs in EV battery gigafactories in red districts? Sure. But what have you done for me lately?)