What Does Elon Musk Want? Abundance. It Makes Strange Bedfellows.

Ezra Klein, AOC, David Sirota, and Aaron Bastani are arguably on the same side as Musk, and that's awkward. Imagination Deficit Disorder, Part II, Chapter 2

This is Part Two of a Whole Thing

You don’t have to, but you might want to check out Part I:

Part II

“It’s tough to make predictions. Especially about the future.” - Yogi Berra

More years ago than I care to count I found myself in a boss-level-nerd summer course on “futurism”.

If you want to judge the likelihood of any future scenario, the lesson plan said, there are only three basic questions:

Is it possible?

Is it preferable?

Is it profitable?

Even aged 13, my annoying question to the teacher was, “for who?”1

And even if Who Framed Roger Rabbit? isn’t to your taste2, you don’t need to look very hard to find examples of potential futures that were spiked for reasons that had everything to do with the answer to that question.

My favourite story in that vein was recently popularised by Dr Sugandha Srivastav at Oxford. She wrote about Canadian inventor George Cove, who seems to be the first to have cracked solar PV.

Two problems:

One, when Cove was deploying it on New York rooftops, he couldn’t properly explain why it generated electricity – because it was in 1909, and the term “quantum physics” wouldn’t be coined for another 15 years.

Two, in 1909 he disappeared. When he re-appeared, Cove claimed he’d been kidnapped, held captive, and told to stop his research. Or else. And then released into the Bronx Zoo.

Sugandha made news by sketching out how much sooner the world might have arrived to the point of solar PV being as low-cost and viable as it was in 2024, had Cove continued his work. I put the question to her in an episode of Wicked Problems last year. How much sooner? Decades, she said.

Are speculations about potential futures, including those that might have been but were prevented or delayed, useful?

As delightfully dyspeptic GWU political communications professor Dave Karpf put it on Bluesky recently, reviewing a book we’ll come back to shortly:

“Futurism was a significant (and flawed) part of the public discourse for much of the 20th century.

I read Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock a couple months ago. It was a 1970 bestseller. Huge deal. Completely bonkers book.

Today instead of futurists offering sage advice to the power elite, we have power elites (Musk, Thiel, etc) acting as futurists.

That’s clearly bad.

But I haven’t seen much attention paid to why and how that old futurism faded and failed. I’m not certain that bringing it back would do much good.”

As we described in Part I, Musk and Thiel “acting as futurists” doesn’t happen in a vacuum. There is plenty of evidence that their thinking – or at least their rhetoric – about the future has been shaped by the sci-fi (and other sources) they consumed. And plenty have reacted to that.

These reactions generally fall into two camps.

One is best represented by (sci-fi author) Charles Stross in his 2023 Scientific American essay, “Tech Billionaires Need to Stop Trying to Make the Science Fiction They Grew Up on Real”.

Science fiction… does not develop in accordance with the scientific method. It develops by popular entertainers trying to attract a bigger audience by pandering to them. The audience today includes billionaires who read science fiction in their childhood and who appear unaware of the ideological underpinnings of their youthful entertainment: elitism, “scientific” racism, eugenics, fascism and a blithe belief today in technology as the solution to societal problems.

To buttress his point, Stross quotes philosopher Émile Torres, who works on existential threats to humanity, and is a cracking Bluesky follow. Stross summarises Torres’ work in trying to systematise a weird Silicon Valley elite belief system they see, informed by copious scifi and fantasy lit, which Torres calls TESCREAL:

which stands for “transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, rationalism, effective altruism and longtermism.” These are separate but overlapping beliefs in the circles associated with big tech in California. Transhumanists seek to extend human cognition and enhance longevity; extropians add space colonization, mind uploading, AI and rationalism (narrowly defined) to these ideals. Effective altruism and longtermism both discount relieving present-day suffering to fund a better tomorrow centuries hence. Underpinning visions of space colonies, immortality and technological apotheosis, TESCREAL is essentially a theological program, one meant to festoon its high priests with riches.

Stross points also to a slightly pithier 2021 post from Alex Blechman:

The opposing camp could be said to be most thoughtfully represented by Noah Smith in a rapid rebuttal, “In defense of science fiction; New technology is usually good, and it's good for sci-fi to inspire it.”

Responding to another member of Team Stross, Smith asks whether tech billionaires got their ideologies from scifi or whether they were attracted to particular stories (but not others) because, as Stross writes, they pick authors they feel already agree with them. Smith goes on to nail something important for this parish:

…No, climate fiction won’t solve climate change, but might it not have stirred the imagination of the scientists and engineers who invented and refined solar power and batteries — the two technologies with the greatest chance of replacing fossil fuels? Without those green energy technologies, the world would face a bitter choice between runaway climate change and degrowth. But thanks to technologists, we no longer face that tradeoff. If those technologists were inspired by sci-fi, that’s a pretty huge win for the genre.

Wicked Problems and your humble correspondent have been open about our normative bias. We try and talk to activists, sceptics, policy wonks and others who fundamentally disagree with the idea that (strawman) “technology and markets will save us” or even the harder case - (steelman) “restless innovation is what allowed the species to thrive to this point and to say it has no role in creating a better future is at best disingenuous”. We hugely enjoy talking to the ones who engage in that critique in good faith, and they are reliably among our most popular episodes. We tend to avoid the ones that engage in bad-faith, ad hominem, and ultimately unserious takes on the subject. We are too old and too ugly to waste time on that, even for spectacle/clicks, because time really does feel short.

Excellent example of - for us - what good looks like is from an unforgivably long-delayed forthcoming episode recorded last year with strategist and author Patrick Reinsborough, on the related phenomenon he calls “Marsification” -

Marsification is a first step at trying to name part of the deep irony of the of the world that we live in an important narrative strategy is to make the invisible visible. The most powerful narratives that operate are often just assumed as common sense, and a lot of what I believe has led our civilisation to this epic point is these unexamined narratives that fuel a very destructive economic model.

Marsification is a word intended to capture that phenomenon. This obsession with colonising Mars, this fantasy that we're going to turn Mars into Earth, is actually distracting us from what's actually happening. Not to overstate it, but we're kind of turning Earth into Mars, and so this is very central to what's happening.

And from a narrative perspective, how do you name that technology will save us narrative? Again, not to say that technology doesn't have a role to play, but the techno-salvationist narrative, it's so transparently absurd to anybody who looks at it, [particularly] about the idea of Mars as a solution to Earth's ecological crisis.

The balance of this essay is not about whether scifi is good or bad, or whether it’s a distraction. Nor is it about whether it is good or bad that tech ‘broligarchs’ are influenced by scifi. What we are attempting to do is point out that referring to ‘tech broligarchs’ as a “they” who monolithically share an ideology might feel like good political rhetoric but is actually unhelpful. Because as we will discuss there are serious differences in the types of stories these characters are drawn to, the values those stories/myths encode and either reinforce or in their pedagogical function help some form for the first time, how the preferences of that select class of readers might be predictive (or just explanatory) of things they’re doing where the reasons are either deliberately concealed or aren’t obvious, and how to understand the appeal of those stories to the people who admire and follow these characters.

Whether these characters are faithfully representing the works they say they’re inspired by is a whole other thing. It’s one we won’t dwell on (it’s why the ideas gain traction, not the sincerity of their evangelists, that matters, IMO). But it would be remiss not to acknowledge that critique.

It is unlikely Ursula Le Guin would look kindly at how science fiction is harnessed by these parvenu “power elites”. Introducing The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin wrote:

“Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.

Predictions are uttered by prophets (free of charge), by clairvoyants (who usually charge a fee, and are therefore more honored in their day than prophets), and by futurologists (salaried). Prediction is the business of prophets, clairvoyants, and futurologists. It is not the business of novelists. A novelist's business is lying.”

One might quibble with this, if we may be so bold. Or at least echo Noah Smith in suggesting it’s not the whole story, even if authors rightly want to indemnify themselves from the charge they’ve given instruction manuals to monsters when they meant no such thing.

The relationship between scifi and stuff that gets built isn’t simple or one-way. Without Arthur C. Clarke’s 1945 thought experiment would there be geostationary satellite comms? Star Trek TOS communicators to mobile phones? Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon to cryptocurrency? Ray Bradbury’s (not-yet-fully-realised) self-driving car? 3

Or, for the more abstract point, when in the above Le Guin novel, it’s put to her alien character Estraven that inventing powered flight would have solved a lot of problems on his planet, Estraven (who was brought up in a world with no winged creatures) replies:

“How would it ever occur to a sane man that he could fly?”

How, indeed.

The larger point is crucial. Most scifi writers, force-fed a litre of whiskey and with bamboo under their fingernails, with the likely exception of Three Body Problem author Liu Cixin - who must look over his shoulder at what the Chinese Communist Party thinks he is really saying, will agree with Le Guin. Scifi offers the plausibility at least that one is not describing current problems - in a non-threatening way to the existing order, exploring themes while having plausible deniability for any political implications a reader may think they spot in the text.

Non-crap sci-fi as a thought experiment on Le Guinnian lines is a tradition stretching from Schrödinger’s cat back to Plato’s cave and Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality. It’s never about ET. It’s about us. It’s a [black] mirror, not a crystal ball. And sometimes is a plea of “don’t fuck this up”, in some plausible extrapolation of present foibles.

Neither Thiel nor Musk have been accused of Le Guin-level subtlety of thought or alchemy with language. Indeed, Jill Lepore devoted an episode of her 2021 Musk “Origin Story” series for the BBC to the whole canon of female science fiction writers that she felt Musk had ignored – and implied he might have benefitted from exposure to – including Le Guin.

With an animus that fizzes out of the speaker, Lepore maintains that Musk was immune to any irony of the scifi he did consume and remains stuck in some worst version of Robert Heinlein stories, a future that is hypercapitalist, fuelled by hyper-try-hard-masculinity, and stuck in a vision of gleaming spaceships, colonisation, and a “we come in peace/shoot to kill” ethos.

I’m certainly no Jill Lepore, with a glittering career at Harvard and The New Yorker, and no serious person should argue that Musk does not have some pretty complicated issues around gender and family that his wealth and influence have (tragically) made sure to cast a long shadow over global culture.

But for the purposes of this essay, let us stipulate a few things.

One, Thiel and Musk are not standard-issue dudes. This IN NO WAY gives them a pass. In a later chapter we’ll come to a new game I’ve developed and we’re workshopping for the show, which as a late-diagnosed neurodivergent and parent of another I claim the right to offer (describing actions, not people): “Aspie, or Asshole?”

Two, Musk in particular has used the political power he purchased to do objectively bad shit, and when all is said and done he may have killed more people than – as someone wrote but I can’t find the source to attribute – Putin, Hamas, and the IDF, combined. Thanks to cutting off tens of millions of people from live-saving aid for things like HIV drugs via PEPFAR. If there’s a Hell, he’s reserved a prime sun lounger.

Three, that because of their unprecedented wealth and concomitant power, the motivations and objectives of these characters are more urgent than ever for us to understand. Even if you think that they’ve had their day because of people doing a victory dance every time there’s a minor reversal in their programme. Because many have thought that before. Whether sincere or not, the stories they (re) tell about the future have influenced an entire generation. The stories, not just their tellers, are powerful.

Four, that Lepore and others – I offer with all humility – have missed a key point or two about those influences, that those are worth exploring, and we will argue that in the balance of this essay.

Musk may be more Thanos than Iron Man. But the Avengers scriptwriters gave Thanos a sincere belief that because what he was doing was necessary, and for the best, it justified genocide, ecocide, and whatever you call killing half of all life in the universe. The line between superhero and supervillain is jagged and studded with mirror fragments.

You don’t have to admire how they see themselves. The more important point is that you turn your back on people in power who believe in the ends and the means of such things at your (and my) peril.

2. Abundance

“Theirs is a civilisation of deprivation; ours of finely balanced satisfaction ever teetering on the brink of excess” – Iain M. Banks, The State of the Art (1989)

If you had cause to listen to the Tesla conference call of 22 April, announcing a 71% fall in quarterly profits year-on-year, quicker than a Model S can smoke a Porsche 911 going from 0-60, largely down to brand damage inflicted by their CEO, Elon Musk, you may have noticed how wounded Musk sounded.

To say Elon Musk has journeyed from ‘Iron Man’ techno-optimist pinup to “Swasticar” hate figure is not to say anything new or interesting. Otherwise sensible people revelling in the brand destruction of Tesla are bogeying fat lines of well-earned Schadenfreude4. Some also – incorrectly – suggest Musk is delusionally unaware the link between his going all-in for Trump, his DOGE role, and the impact on Tesla sales and profits.

If we have any hope of understanding the appeal of the people we see as working against our values or goals, the first step is to stop telling ourselves things that are manifestly untrue.

Literally the first thing Musk said on the call was, “As people know, there’s been some blowback for the time that I’ve been spending in government with the Department of Government Efficiency or DOGE.”

It’s not like this was hard to see coming. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, in Abundance: How We Build A Better Future [‘Abundance’, hereafter], published in March just a few weeks after Trump’s inauguration, (thankfully for the authors) still time to get in this line before the print run:

“Elon Musk has led some of the most innovative companies of the modern era, but according to the earliest reports of his role in Trump’s government, he is focused on slashing what government does rather than reimagining what it can do. The right is abandoning many of its successes to embrace a politics of scarcity.”

Klein in particular has, for quite a long time across many of his interviews, made the point that – particularly, but not solely, in a democratic system – the politics of scarcity is a loser.

What do Klein and Thompson mean?

“Scarcity is a choice…

“This book is dedicated to a simple idea: to have the future we want, we have to build and invent more of what we need. That’s it. That’s the thesis.”

“Abundance” has found greater salience in part due to Klein & Thompson’s book, but their book is framed as an attempt to bring coherence and political utility to an existing trend, rather than inventing something wholly new.

It’s a little bit noisy, but the above Google search data from the US shows a steady increase, once you account for seaonality. Perhaps not surprisingly, ‘abundance’ has a strong seasonal component. Searches rocket from the end of August through mid-September and tail off during the harvest before (in the US) spiking again around Thanksgiving. Because farms. But there’s a measurable upward drift that is accelerated in March 2025 when “Abundance” is published.

A few days ago in the New York Times, Adam Tooze offered a sideways review of “Abundance” nestled in his article purportedly a review of What’s Left: Three Paths Through the Planetary Crisis, by Malcolm Harris - an analysis of the climate crisis that makes Andreas Malm sound like a dewy-eyed Panglossian, at least in terms of the plausibility of solutions most people are willing to discuss:

The key insight of “What’s Left” is that these three approaches, rather than being mutually exclusive, actually all need one another: “Public power needs the radical threat; communists need bail money; marketcraft needs an organized working-class constituency.”

In many ways, Harris might be thought of as the left-wing alter ego to the liberal journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. In their recent policy book “Abundance,” they too seek economic renovation and human thriving by encouraging innovations in clean energy and transportation. Like Harris, they also suggest a liberal-to-left coalition, inspired by the futurist spirit of Marxist political tracts like the radical podcaster Aaron Bastani’s “Fully Automated Luxury Communism.”

We’ll come back to Bastani in a minute.

For the “abundance” discourse, its nemesis is “scarcity”. Americans have increasingly come to worry about scarcity, insofar as search volume has any meaning (your mileage may vary). Since COVID in particular and in general building through the lingering effects of the 2007-09 global financial crisis. Here’s data from the same source:

The big peaks are Sep. 2020 – when COVID supply chain crunches really started to bite – and Jan. 2024 (because this is US data, we might speculate “eggs” had something to do with the latter spike, but that’s just a guess). The slow build up correlates with the progressive deformation of American public life into one where Donald Trump makes sense.

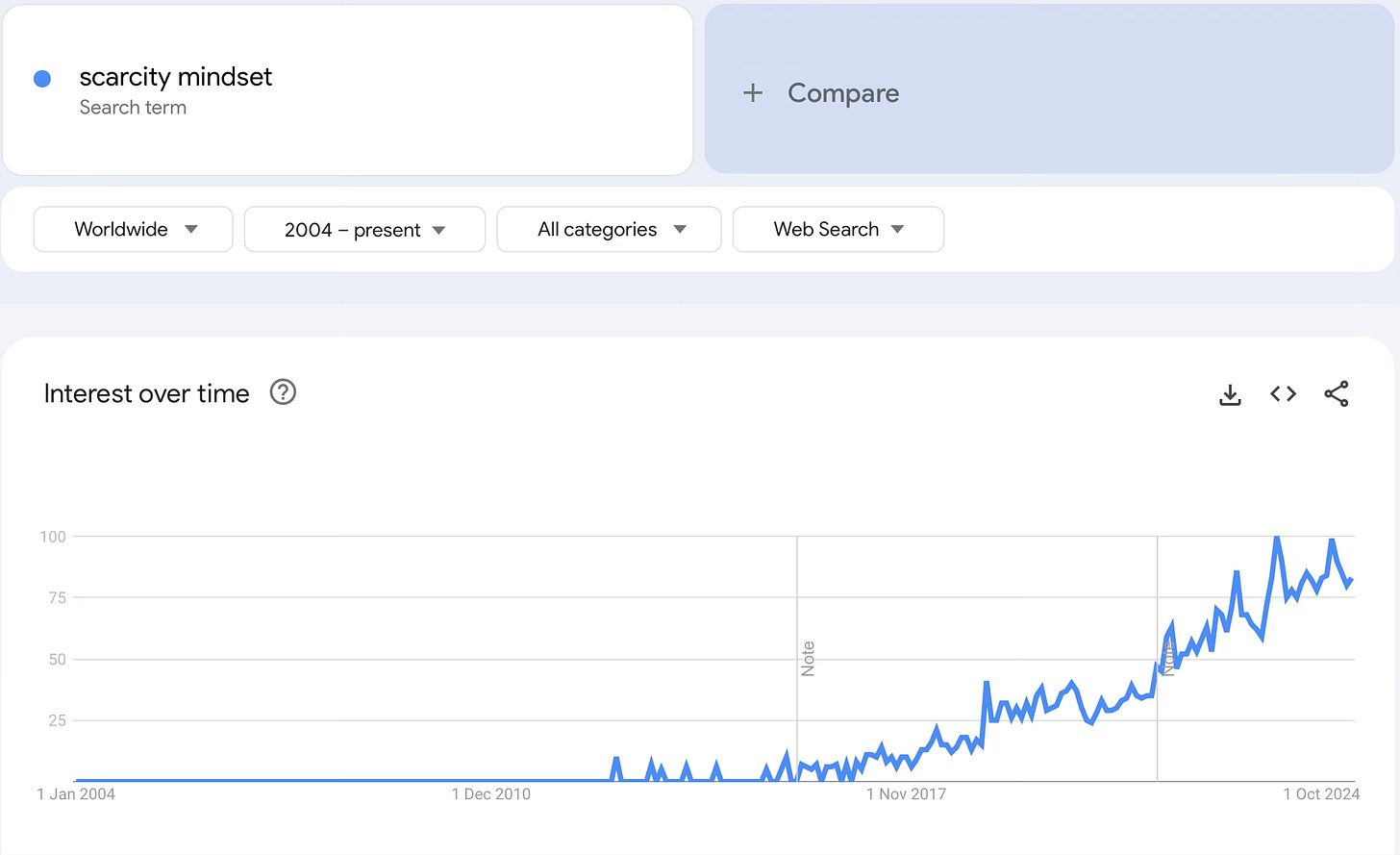

When we zoom in and try to go a bit less generic, we might try different search terms: “scarcity mindset” and “abundance mindset”.

“Scarcity mindset” began getting traction in 2019, not least because of its use by newly-elected New York City member of Congress, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. In response to a heckler:

(Until my kids’ primary school parents’ evening here in the UK 15 years ago, I’d never heard the word “mindset” used unironically.)

Some on the [anarcho-capitalist] ‘right’, like Patrick Carroll, then managing editor at the Foundation for Economic Education in 2022, took AOC and others to task for using the phrase. In part because, according to Carroll, both phrases trace back to self-help books such as Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People and advice on negotiation. Short version: if you imagine your negotiation as possibly a non-zero-sum game, you will be more likely to find a “win-win” outcome.

If one isn’t writing a polemic and trying to discredit the idea as shallow, recent, and reeking of therapeutic self-help books, one could wind back a bit further to furious reactions to the Club of Rome’s 1972 “Limits to Growth”, to Galbraith, or JFK’s “rising tide lifts all boats” speech, or John Maynard Keynes5, or Fredrick Jackson Turner’s 1893 Frontier Thesis, or anyone who thought Thomas Malthus was full of shit. One could even point to — as Bloomberg’s Liam Denning did in 2019, citing Edmund Morris’s biography published that year — Thomas Edison’s understanding of why clean energy will be the ultimate example of the flip scarcity to abundance:

“Sunshine is a form of energy, and the winds and tides are manifestations of energy. Do we use them? Oh no; we burn up wood and coal, as renters burn up the front fence for fuel. We live like squatters, not as if we owned the property.”

But if you grant both that this is not a purely new discourse and that reframing it in language that resonates with a contemporary audience is not just justified but useful, the difference is dramatic:

Ezra Klein is not saying anything revolutionary. If you tell people a story that ends in abundance, and in particular a solarpunk utopian abundance for all, that is a winning political message. For him. For AOC. For anyone who tells a story about how the future can be better than the past - because the disease of the West is the quite recent failure for non-insane, non-fascist people to offer an inclusive vision of what such a future could look like and a politics of how to get there.

The alternative, which we will discuss in the next chapter, is some dark shit about how to have the sharpest elbows and ensure that your family/tribe/nation/race maximises their cut of a pie that is shrinking, not growing.

This is where it gets tough for Klein, Thompson, AOC, David Sirota, and anyone else loosely aligned to the ends - not a particular set of means - of an “abundance” agenda. Because the most prominent advocate for the abundance agenda is the same person who has come to embody the wilful destruction of any remnant of things good and sane and right in American governance.

Elon Musk.

It’s the meth-dream version of the “worst person you know makes a good point” meme.

On that Tesla earnings call this week, at the end of his opening remarks, he went back to something clearly prepared earlier. Something that chimes with a theme he has been using for a good few years now, externally and internally:

“In conclusion, while there are many near term headwinds for us in the broader industry, the future for Tesla is brighter than ever. The value of the company is delivering sustainable abundance with our affordable AI powered robots… I like this phrase, sustainable abundance for all. If you say, like, what’s the ideal future that you can imagine?

That’s what you’d want. You’d want abundance for all in a way that’s sustainable. It’s good for the environment. Basically, this is the happy future. So what’s what’s the happiest future you could imagine?

One which is that would be a future where there’s sustainable abundance for all. Closest thing to heaven we can get on earth, basically.”

A bit like having a perpetually off-his-meds racist uncle that you find yourself agreeing with on something over the holidays, it’s tough cognitive territory to navigate.

Here is why.

When promoting “Abundance” in a March New York Times column, Klein was crystal clear about his motives, and I think dead-right in his analysis:

The populist right is powered by scarcity. When there is not enough to go around, we look with suspicion on anyone who might take what we have. That suspicion is the fuel of Trump’s politics. Scarcity — or at least the perception of it — is the precondition to his success.

No one in this parish will argue that producing a polemic to instruct others about the best arguments to defeat nascent facism are not valuable. Quite the opposite. But we choose to go a bit upstream.

The question I’m more interested in for this essay - and if you’re not, step off the merry-go-round now - is less whether the framing of the future such stories of abundance are politically effective (certainly, at least in America, they are) or whether they are “predictive” in Le Guin’s sense, than whether they are ‘helpful’ in either discerning an ‘inevitable’ vs merely ‘possible’ future. Where they may have predictive value, it will reside in helping understand actions of those in power who believe those futures are inevitable.

Opposing ideas of politics - or I suppose the political economy - who take it as their project to bring about a vision of the future their storytellers can imagine and find appealing - matter quite a bit. As Klein continued in the same piece:

The answer to a politics of scarcity [emphasis included] is a politics of abundance, a politics that asks what it is that people really need and then organizes government to make sure there is enough of it. That doesn’t lend itself to the childishly simple divides that have so deformed our politics. Sometimes government has to get out of the way, as in housing. Sometimes it has to take a central role, creating markets or organizing resources for risky technologies that do not yet exist.

Politics - systems determining who has the power to bring about the future they want - is that annoying “For who?” question we started with. It’s not possible to disentangle the politics from the stories. But people arguing for a particular future might find it valuable to spend a bit of time exploring the stories before jumping to abstractions of politics that depend upon them.

Elon and Abundance Culture

The late Scottish sci-fi author Iain M. Banks, as far as we know, never met Elon Musk. But Elon certainly feels like he understood Banks, and how his fiction shapes his vision of the future:

"I'd recommend people read Iain M. Banks. The Banks Culture books are probably the best envisioning. In fact, not probably, they're definitely by far the best envisioning of an AI future. There's nothing even close. So, I'd really recommend Banks. I'm a very big fan. All his books are good. It doesn't say which one – all of them. That'll give you a sense of what is, I guess, a fairly utopian or protopian future with AI."

From an interview with Rishi Sunak, 2023

Unlike scifi writers like Neal Stephenson6, who was happy to distance himself from Mark Zuckerberg’s appropriation of “metaverse” from Stephenson’s breakthrough anarcho-capitalist cyberpunk dystopian thriller Snow Crash - while also working as a ‘futurist’ consultant for Jeff Bezos, Banks doesn’t seem the sort who would be palling around with billionaires.

And because he died in 2013, we can’t ask him what he thinks of Musk, or whether Musk ever tried to get in touch. By then Musk had become pretty famous, so it’s hard to imagine Banks was completely unaware of his rise or his often-mentioned penchant for sicfi.

Walter Isaacson’s bio provides a concise version of Musk’s own account of how he came to immerse himself in scifi when growing up in South Africa:

Elon came to believe early on that science could explain things and so there was no need to conjure up a Creator or a deity that would intervene in our lives.

When he reached his teens, it began to gnaw at him that something was missing. Both the religious and the scientific explanations of existence, he says, did not address the really big questions, such as Where did the universe come from, and why does it exist? Physics could teach everything about the universe except why. That led to what he calls his adolescent existential crisis. “I began trying to figure out what the meaning of life and the universe was,” he says. “And I got real depressed about it, like maybe life may have no meaning.”

Like a good bookworm, he addressed these questions through reading. At first, he made the typical mistake of angsty adolescents and read existential7 philosophers, such as Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Schopenhauer. This had the effect of turning confusion into despair. “I do not recommend reading Nietzsche as a teenager,” he says.

Fortunately, he was saved by science fiction, that wellspring of wisdom for game-playing kids with intellects on hyperdrive. He plowed through the entire sci-fi section in his school and local libraries, then pushed the librarians to order more.

One of his favourites was Robert Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, a novel about a lunar penal colony. It is managed by a supercomputer, nicknamed Mike, that is able to acquire self-awareness and a sense of humour. The computer sacrifices its life during a rebellion at the penal colony. The book explores an issue that would become central to Musk’s life: Will artificial intelligence develop in ways that benefit and protect humanity, or will machines develop intentions of their own and become a threat to humans?8

In the many articles and podcasts about Musk’s relationship with scifi, many focus on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy or Asimov’s Robot and Foundation stories. But while Musk has, to our knowledge, not tried to create an “Improbability Drive” ala Hitchhiker’s Guide, he seems to have been quite taken around 2014 with The Culture novels.

The novels are set some 9,000 years in the future, and “The Culture” is a humanoid multi-species galaxy-straddling civilisation of 30 trillion people. Many of the books focus on the interactions between the Culture and those with less advanced technology or different values.

In Use of Weapons (1990), here’s how Banks has his protagonist, Zakalwe - a rogue freelance mercenary working loosely for the Culture’s black ops organisation Special Circumstances - describes it to a leader of one of these less developed civilisations:

“Once upon a time, over the gravity well and far away, there was a magical land where they had no kings, no laws, no money and no property, but where everybody lived like a prince, was very well-behaved and lacked for nothing. And these people lived in peace, but they were bored, because paradise can get that way after a time, and so they started to carry out missions of good works; charitable visits upon the less well-off, you might say; and they always tried to bring with them the thing that they saw as the most precious gift of all; knowledge, information; and as wide a spread of that information as possible, because these people were strange, in that they despised rank, and hated kings…”

Described variously as “utopian” and “anarcho-communist”, the Culture’s post-scarcity world is made possible by vastly superior AIs called “Minds” and ubiquitous robotics - who collectively find the descendants of their human creators sort of cute pets who are indulged. AI runs the show. Why the AI ‘Minds’ didn’t wipe out humans altogether is unclear, other than that they tend towards being nice. They also tend to have a fairly wicked sense of humour and seem to enjoy watching what those kooky humans get up to.

Culture humans amuse themselves with lavish sex lives, body enhancements of “genofixed” glands that can produce drugs with a thought, frequent gender changes over very long lives, and seeing other civilisations as hobbies and distractions in a way not dissimilar to the way the AIs see them.

Not everyone is thrilled with this arrangement - and not merely because of boredom. In fact, in the first of the novels, Consider Phlebas (1987), Banks’ protagonist, Horza, is a self-described humanoid enemy of the AI setup who so hates the Culture that he works as an agent for the Idirans, a brutal imperialist species steeped in religious fundamentalism, cruelty, and genocide, with which the Culture is engaged in its first war in millennia. Horza explains his thinking in words that despite being written in the early 80s could easily be found in Bluesky posts about LLMs:

“I don’t care how self-righteous the Culture feels, or how many people the Idirans kill. They’re on the side of life—boring, old-fashioned biological life; smelly, fallible, short-sighted, God knows, but real life. You’re ruled by your machines. You’re an evolutionary dead end.”

It sounds a bit like the speech from Calcagus (as imagined by Tacitus), in describing the Romans the doomed Celtic chieftain is fighting to resist:

the only people who behold wealth and indigence with equal avidity. To ravage,

to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make

a desert, they call it peace.

Horza also voices the more contemporary fear of AI (or more specifically AGI). That the machines might decide they’re better off without us:

“He could not believe that ordinary people in the Culture really wanted the war, no matter how they had voted. They had their communist Utopia. They were soft and pampered and indulged, and the Contact section’s evangelical materialism provided their conscience-salving good works. What more could they want? The war had to be the Minds’ idea; it was part of their clinical drive to clean up the galaxy, make it run on nice, efficient lines, without waste, injustice or suffering. The fools in the Culture couldn’t see that one day the Minds would start thinking how wasteful and inefficient the humans in the Culture themselves were.”

Why would a man, arguably the world’s leading capitalist, who seems obsessed with wealth, power, and a hatred of transgenderism produced by “the woke mind virus” be so attracted to a fictional universe of woke gender-fluid communists who have outgrown money and status?9

One common answer - so common it brought together The Guardian and The Telegraph - is the suggestion that Musk doesn’t understand that stories he reads. It’s been echoed by many, including Jill Lepore, who got quite audibly exasperated when describing Musk’s supposed misunderstanding in a recent New Yorker Political Scene podcast in conversation with David Remnick. Other scifi authors, like Stross above or Cory Doctorow, seem outraged on Banks’ behalf:

Stuart Kelly in 2018, writing in the Guardian:

So, Elon Musk has claimed he is a “utopian anarchist” in a way he claims is best described by the late science fiction author Iain M Banks. Which leads to one very relevant question: has Musk actually read any of Banks’s books?

Ed Power in 2022, in the Telegraph, with the headline, “Elon Musk is inspired by Iain Banks’s utopian sci-fi novels – but he doesn’t understand them”

subhed: “The billionaire says he’s ‘a utopian anarchist of the kind described by Iain M Banks’ – but what of Banks’s socialist and anti-wealth views?”

Banks’s Culture books are spry, dense, provocative and mind-bending – and also a conduit for the author’s essentially hardline socialist beliefs and the idea of the collective good as the ultimate value society should wish to uphold. Described by Banks as “hippie commies with hyper-weapons and a deep distrust of both Marketolatry and Greedism”, the Culture is ultimately a force for good in the universe.

Power also had a take on what, if anything, the author would think of how his work was being used by Musk:

…Banks wo uld also have needed a moment to compose himself were he to learn that his sci-fi novels were beloved by the Tesla boss. Or that Musk has patterned much of his career on the writing of Banks

More recently, Sam Freedman put it like this in The Guardian:

One can only imagine the horror the late Iain Banks would have felt on learning his legendary Culture series is a favourite of Elon Musk. The Scottish author was an outspoken socialist who could never understand why rightwing fans liked novels that were so obviously an attack on their worldview.

Stuart Kelly, who interviewed Banks right before his death in 2013, reflected on a darker possibility. Not that Musk doesn’t understand it, but that he understands it all too well - it’s most of the rest of the audience who doesn’t:

“the Culture would stay until everything else in the universe was like them. Not exactly utopian, not exactly anarchist.

So it is worrying that a tech entrepreneur thinks that a totalitarian, interventionist monolith is a role model. If there is an afterlife, Banks must be laughing his cotton socks off.”

We’ve spent enough time on the “What would Banks think?” parlour game, which is quite fun. Let’s look at how, as Power says, Musk seems to have taken some of the ideas in the Culture novels and run with them. Because this is where I think it gets quite interesting, and once you see his actions in context, a pattern might suggest itself.

OpenAI, Neuralink, xAI, SpaceX, Grimes

Not long after tweeting his love of Banks’ Culture novels, something did seem to change. He co-founded OpenAI with Sam Altman as a non-profit in 2015.

OpenAI’s founding mission was to ensure that, should it happen, a future AI superintelligence would be more like Just Read the Instructions quirky Culture starships and less like Terminator’s Skynet or The Matrix:

“to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity."

In 2016, Musk co-founded Neuralink, his startup working on a Brain-Computer-Interface to connect human “wetware” to computer “software”. He called the device a “neural lace” - something directly lifted from a recurring feature of the Culture novels.

Tim Urban probably has the definitive account of Musk’s thinking on the topic in his book-length waitbutwhy essay, after spending time with Musk and the Neuralink founding team. His quotes of Musk are in italics:

the more separate we are—the more the AI is “other”—the more likely it is to turn on us. If the AIs are all separate, and vastly more intelligent than us, how do you ensure that they don’t have optimization functions that are contrary to the best interests of humanity? … If we achieve tight symbiosis, the AI wouldn’t be “other”—it would be you and with a relationship to your cortex analogous to the relationship your cortex has with your limbic system.

Elon sees communication bandwidth as the key factor in determining our level of integration with AI, and he sees that level of integration as the key factor in how we’ll fare in the AI world of our future:

We’re going to have the choice of either being left behind and being effectively useless or like a pet—you know, like a house cat or something—or eventually figuring out some way to be symbiotic and merge with AI.

Then, a second later:

A house cat’s a good outcome, by the way.

Without really understanding what kinds of AI will be around when we reach the age of superintelligent AI, the idea that human-AI integration will lend itself to the protection of the species makes intuitive sense. Our vulnerabilities in the AI era will come from bad people in control of AI or rogue AI not aligned with human values. In a world in which millions of people control a little piece of the world’s aggregate AI power—people who can think with AI, can defend themselves with AI, and who fundamentally understand AI because of their own integration with it—humans are less vulnerable. People will be a lot more powerful, which is scary, but like Elon said, if everyone is Superman, it’s harder for any one Superman to cause harm on a mass scale—there are lots of checks and balances. And we’re less likely to lose control of AI in general because the AI on the planet will be so widely distributed and varied in its goals.

But time is of the essence here—something Elon emphasized:

The pace of progress in this direction matters a lot. We don’t want to develop digital superintelligence too far before being able to do a merged brain-computer interface.

When I thought about all of this, one reservation I had was whether a whole-brain interface would be enough of a change to make integration likely. I brought this up with Elon, noting that there would still be a vast difference between our thinking speed and a computer’s thinking speed. He said:

Yes, but increasing bandwidth by orders of magnitude would make it better. And it’s directionally correct. Does it solve all problems? No. But is it directionally correct? Yes. If you’re going to go in some direction, well, why would you go in any direction other than this?

And that’s why Elon started Neuralink.

Here’s Urban’s diagram (no, you’re not hallucinating this, he compares ‘neural lace’ to a wizard’s hat):

Whether the tech ultimately will succeed is anyone’s guess. And in November of last year the company announced it had received approval from Health Canada to launch its first international trial of testing its “neural lace” on disabled volunteers without use of their limbs, to try and manipulate a robotic arm with just thought.10 It followed two human implants in US test subjects.

The company’s product branding has slightly moved on from its original nomenclature. A year after its first human trial, it now refers to its three clinical trial subjects as people with “Telepathy”. One patient with a devastating spinal cord injury appears in a recent testimonial video:

Musk’ association with OpenAI and Altman didn’t last, however.

Building all the “compute” to create the models that would eventually become ChatGPT took a lot more capital than a nonprofit’s donations were likely to achieve.11 So Musk and Altman had a spectacular divorce in 2019. Musk, the story goes, wanted to accelerate OpenAI’s move to a for-profit company. Altman wanted to set up a for-profit subsidiary that the non-profit would ostensibly still control while allowing it to raise the required vast sums of capital.

Musk lost the power struggle and went off in a huff. Altman brought in investment from Softbank and Microsoft, with the latter having a unique profit-sharing arrangement. When ChatGPT becomes profitable, Microsoft will get the lion’s share of profits until it receives $13 billion. After that it is to receive 50% of the profits until a cap of $92 billion.

So in 2023 Musk launched the rival “xAI” with some $1 billion in funding and the FT reported in May 2024 that xAI had new investors:

Elon Musk’s xAI has secured new backing from Silicon Valley venture capital giants Lightspeed Venture Partners, Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia Capital and Tribe Capital, as the tech billionaire closes in on a [$6 billion] funding round valuing the artificial intelligence start-up at $18bn.

In February of 2025, xAI made a bid to buy OpenAI for nearly $100 billion. It was rebuffed. But may slow down Altman’s plans to do exactly what Musk wanted OpenAI to do years before, move to a less complicated corporate structure with more profit focus.

The BBC quoted Cornell University senior lecturer Lutz Finger’s take:

“Musk has missed the AI train, somewhat. He's behind, and he has made several attempts to catch up," Mr Finger said.

Now, Mr Finger says, Mr Musk is trying to kneecap his most formidable competitor.

And then in March, Musk announced that the social media platform X (nee Twitter) had been folded into xAI in a net $33 billion all-stock deal that some pointed to as a way of extracting value from a Twitter acquisition that to many seemed a spectacular failure. TechCrunch:

One of the major advantages that xAI has over OpenAI and other startups is its access to X. The large body of posts that X has accumulated over the years gives xAI a significant advantage in the race for AI training data. Further, X gives Musk’s AI startup a huge consumer app to reach users in.

Musk has a history of blurring the lines between his many companies, which has landed him in legal trouble before. With xAI’s acquisition of X, the two are now effectively one — and the move suggests that X’s true value may lie in advancing Musk’s broader AI ambitions.

The Naming of Things

Around the same time as he was co-founding OpenAI and Neuralink, Musk had also taken to naming SpaceX hardware Culture ships.

Space.com reported in February 2015:

Late last month, SpaceX's billionaire founder and CEO Elon Musk announced that he had named the company's first spaceport drone ship "Just Read the Instructions." The second autonomous boat, which is under construction, will be called "Of Course I Still Love You," Musk added.

"'Just Read the Instructions' and 'Of Course I Still Love You' are two of the sentient, planet-sized Culture starships which first appear in Banks' 'The Player of Games,'" Tor.com noted last month. "Just as the Minds inhabiting each Culture ship choose their names with care, you have to imagine that Musk did the same here."

Musk also has a penchant for evangelising the novels not just on X but with old “PayPal Mafia” associates such as Max Levchin, who revealed in a March profile interview with Semafor:

AI’s science fiction future

Most of his conversations with Musk are about sci-fi rather than politics, he says, noting that the SpaceX founder got him reading Iain Banks’ Culture novels. They’re about “a post-scarcity society where AI is sentient and capable of discovering new physics and building spaceships for itself, and humans are these species of leisure, and they play games, and do art, and live forever, change genders at will because it’s interesting,” he enthuses.

He doesn’t know whether AI will deliver such a future in his lifetime, but notes that many great innovations of the past 150 years were prefigured by the science fiction written 25 years earlier.

“I love reading this stuff, because it sort of pushes your imagination, but part of it just makes entrepreneurs’ jobs easier,” he explains. “I like reading these books because they tell me what to work on next.”

Perhaps Le Guin and Banks are chatting about this in some afterlife bar.

The Canadian-born singer-songwriter “Grimes” seems to also have been someone who shared Musk’s affinity for scifi in general and Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels in particular.

The pair first got together in the spring of 2018, making it official by coupling up at the Met Gala. It was a major moment in building out Musk’s social cred, and quite the contrast to more recent images, which scream many things but not “cool”.

Since then the two had an on-again/off-again relationship that need not detain us. In 2022 she told podcaster Lex Fridman that Banks’ Culture novel Surface Detail is in her view the best scifi novel ever written:

Three children later, when Grimes and Musk more or less definitively separated, she recorded a breakup song. It’s mentioned in the Isaacson bio12:

“I love you, but I don’t love you,” he told her. She replied that she felt the same. They were expecting another child via a surrogate at the end of the year, and they agreed that it would be easier to be co-parents if they weren’t involved romantically, so they broke up.

Grimes later expressed her feelings in a song she was woking on, “Player of Games,” a fitting title on many levels for the ultimate strategy gamer:

If I loved him any less

I’d make him stay

But he has to be the best

Player of games…

I’m in love with the greatest gamer

But he’ll always love the game

More than he loves me

Sail away

To the cold expanse of space.

Isaacson was either unaware of or uninterested in the connection with the Culture novels. The title of Banks’ second work in the series? Player of Games.

Life Imitating Art

Around the same time as Musk was bogeying the Culture novels (and they are quite moreish once you start), starting companies at least partly in response and falling out with Sam Altman at OpenAI, Aaron Bastani, UK co-founder of the “radical” Novara Media, was writing Fully Automated Luxury Communism. (I mentioned we’d come back to him.)

Bastani cites the transformative potential of tech like AI, renewables, asteroid mining, cell-based meat, and gene editing in terms no less effusive than the wildest-eyed Silicon Valley techno-optimist, cited early in Klein and Thompson’s Abundance:

“What if everything could change?”

“What if, more than simply meeting the great challenges of our time — from climate change to inequality and ageing — we went far beyond them, putting today’s problems behind us like we did before with large predators and, for the most part, Illness? What if, rather than having no sense of a different future, we decided history hadn’t actually begun?”

Any future account of this period will want to note well, of all things, the hastily-scheduled Tesla “All-Hands” meeting on 21 March 2025.

A week before Musk announced xAI would fold the former Twitter into its structure, he stood before an audience at Tesla’s Austin factory and spoke for an hour. Looking and sounding quite sober, geeing up employees who quite understandably might be shaken to see their products go from virtue-signalling devices for Hollywood glitterati to hate-objects targeted by vandalism. He didn’t ignore the burning Tesla in the room:

Um, if you read the news, it feels like, you know, Armageddon. Um, so I was like, I can't walk past the TV without seeing a Tesla on fire. They're like, what's going on? Um, you know, some people it's like, listen, I understand if you don't wanna buy our product, but you don't have to burn it down.

That's a bit, unreasonable, you know, like, uh, like this is psycho. Stop being psycho.

That bit came close to 11 minutes in. The previous time was spent building his theme, a reminder to his employees of the reason many of them probably joined the company, and who quite rationally might be updating their LinkedIn profiles.

“We're not just creating products, we're creating a movement for sustainable energy for everyone. What we're trying to convey is a message of hope and optimism.”

And over the hour, demonstrating some of the salesmanship that got him this far, Musk set out a reiteration of the vision that won him a lot of fans on the upslope of his trajectory.

His first point is the power of solar and battery as an unlocking ‘abundance’ technology. Something in common with Thomas Edison to Ezra Klein, but given its timing - strikingly opposed to the energy agenda of the US administration he is part of:

“my prediction is long term, a majority of power on Earth - in fact, eventually it might be like 90% or more of all power on earth - will be solar panels with batteries. That's my prediction.”

How is that claim so vastly different, lacking entirely any resort to fossil gas or nuclear, from the most optimistic scenarios about a clean energy future?

But this energy abundance is in service to a broader objective, and very different from (but not mutually exclusive with) tackling climate change. It’s how solar-powered AI and robots will deliver the world of The Culture.

how do you pull it all together is, um, you know, where do AI and robots fit in this sort of sustainable energy picture, like, uh… Is that just like some weird side project or, or what, you know. Um, but it's, it's because what we're really aiming for here is maybe a better way to think about it rather than sustainable energy is sustainable abundance for all.

So if you think about like, what is the future that would, what's, what's the most exciting future that you could possibly imagine? Like, what does that future look like? It's worth thinking about that. Just, just think, just in, just, just imagine just future. What does that, that amazing future look like? How about a future where you can have any good or service you want at will?

Um, a future of abundance for all, where really anyone can have anything. It, it sounds impossible. It sounds like surely such a thing cannot be the case. But I'm, what I'm here to tell you is that that will indeed be the case. That the future we're headed for is one where you can literally just have anything you want.

Like if there's a service you want, you'll be able to have it. And, uh, and ultimately everyone in the world will be able to have anything they want. Um, what's key to that is robotics and AI. So once you have self-driving cars and you have autonomous humanoid robots where everyone can have their own personal C3PO and R2D2, but even better than that, that's Optimus.

You can imagine like your own personal robot buddy, uh, that is, uh, a great friend but also takes care of, uh, your house. We'll, we'll clean your house. We'll mow the lawn. Uh, we'll walk the dog. Um, we'll teach your kids. Uh, we'll, we'll babysit. And, and, and we'll also also enable the production of goods and services, uh, basically with no limit.

Um, and when you combine that with su su sustainable energy from the sun and batteries, uh, we can also at the same time also maintain a great, uh, environment. So that's, I think is the future that we, that we want a future where, uh, nobody's, nobody's in need. You can have what you want. Um, and we still, but we still have nature.

We still have, uh, you know, the, the beautiful parts of nature that, that we like. Um, I think that's probably the best future. I can't, I like What other future would you want? I think that's like the cool future and also space travel. Let's not forget that. Um, so if you can have basically anything you want and travel to space and go to Mars, and that would be, that's about as good as it gets.

You know, it's like, that's it. So that's really what we're, what we're trying to do is take the set of actions most likely to lead to a great future for all. So that's what I mean by sustainable abundance. Um, and, uh, the, the, the combination of things that we're making, um, with Optimus and ai com and AI compute will achieve, uh, an age of abundance for all.

How is that future fundamentally different from Fully Automated Luxury Communism or the solarpunk 2050 at the beginning of Abundance? The “for all” is a nice touch to attempt to deflect the obvious attack that such a future is for a privileged elite, but it’s far from the first time Musk has said something similar.

Whether you believe him sincere or not, it’s a message that has power, even if the messenger in this case is fatally compromised.

And indeed while Klein and Thompson are understandably uncomfortable in 2025 associating their agenda with the visions of Elon Musk, Bastani was writing when Musk was a less problematic figure.

So, perhaps not surprisingly, in Fully Automated Luxury Communism Bastani mentions Musk 10 times, Tesla 7 times, SpaceX 28 times.

Not everyone was as impressed with Bastani as Klein and Thompson. Even back as far as 2019, Bastani’s mentions of Musk and “technodeterminism'“ were lambasted by Canadian tech writer Paris Marx [a name that could make anyone believe in nominative, if not techno, determinism]:

Bastani combines an emerging post-scarcity notion with a largely uncritical admiration for billionaire futurism: the visions of the future championed by elite figures like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. That’s where Luxury Communism feels like it hasn’t learned the lessons of the past five years. The left doesn’t need a false future that only differs from the techno-optimism of Silicon Valley, by switching capitalist property relations for communist ones, without considering how that might change the path of human development.

In Bastani’s ideal future, everyone will “lead lives equivalent — if we so wish — to those of today’s billionaires” because “our technology is already making us gods — so we might as well get good at it.” Positioning billionaire lifestyles as the goal at a time when taxing the super-rich into oblivion is becoming a rallying cry makes Luxury Communism feel out of touch.

Marx, and we may come back to them in the next section, is perhaps the most interesting polemicist writing in English since Christopher Hitchens. And I think their analysis has the overlap between the abundance vision ends of Musk, Bastani, Klein & Thompson, and even AOC and David Sirota, dead to rights. Where I think they are badly wrong is in some of their methods to try and prove their points, and their failure to grapple with the core appeal of “abundance”.

I also think Marx may not be fully engaged with a key theme of Bastani - the adequacy or lack of it within existing political systems for coping with the technological revolutions underway.

This is hardly the first time existing political thought has been challenged by technology. Google “Spenglerian gloom”, watch Dr. Strangelove, read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein — these are all reactions to a feeling that technologies have outrun the ability of human systems to cope.

Or go back even further, to Socrates fretting about writing - as a technology - in Plato’s Phaedrus:

[Writing] will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.

A less saccharine passage of Bastani’s book immediately precedes the vision of broad sunlit uplands cited by Klein and Thompson:

“…that future is already here. It turns out it isn’t tomorrow’s world which is too complex to craft a meaningful politics for, it’s today’s [emphasis added].

In attempting to create a progressive politics that fits to present realities this poses a problem because, while these events feel like something from science fiction, they can also feel inevitable. In one sense it’s like the future is already written, and that for all the talk of an impending technological revolution, such dizzying transformation is attached to a static view of the world where nothing really changes.”

Bastani gestures at a concern lurking just out of sight in polite discourse around these technologies - that existing politics and government as we understand it is not up to the challenges. In the next section we’ll talk more about Peter Thiel, who was been pretty open about taking that idea and putting it front and centre, not on the periphery, of thinking about politics.

But if you grant that Musk isn’t just insane, setting Tesla share value on fire like The KLF burning a million pounds in cash for an art project13 —

— or that he’s just corruptly trying to flog Cybertrucks to the State Department or grift Pentagon contracts for SpaceX and Starlink, that does not exclude other possibilities. What if there’s another reason that would at least offer some plausible explanation?

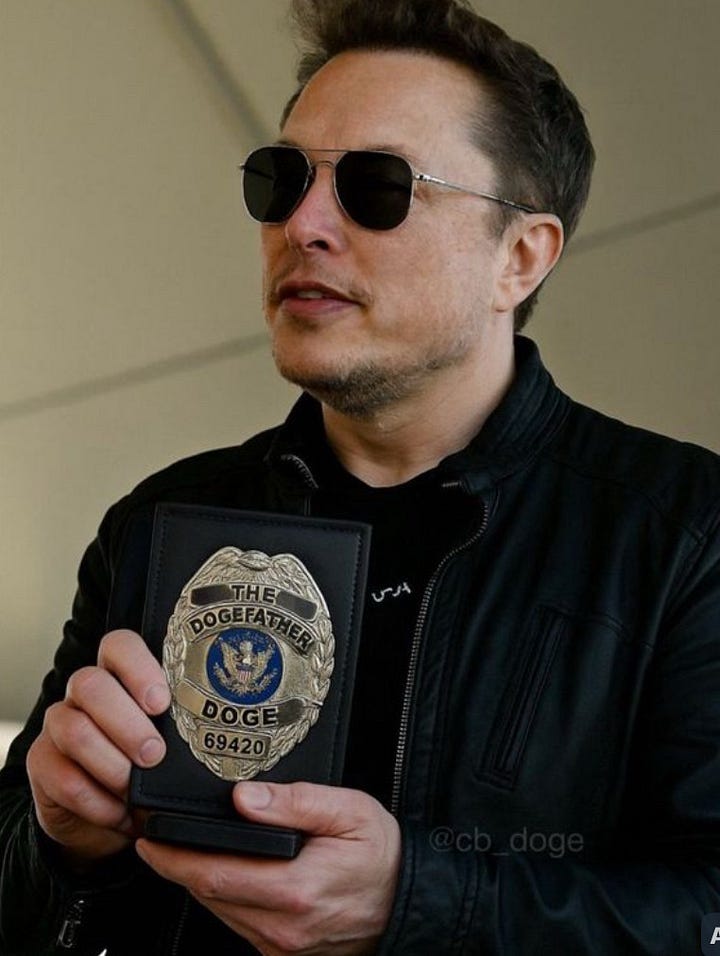

The DOGEFATHER

When it was first announced that Donald Trump’s biggest campaign donor would be coming aboard to help play some role in the new administration, many assumed that Musk would flit about at some Cabinet meetings, get some photo-ops with POTUS, maybe get privileged access to some folk who could advance his varied business interests in space, energy, transport, comms, digital media, biotech, and AI, to name a few.

Instead, much like his old associate Peter Thiel, Musk made clear DOGE wasn’t (just) for photo-ops. Unlike Thiel, Musk wanted maximum attention on what he was doing, ostensibly in the name of “transparency” and cutting “waste, fraud, and abuse” and reducing the US federal budget by $2 Trillion per year to avoid eventual bankruptcy.

On its face it’s fair to say that those stated objectives were somewhat underachieved, costing $135 billion in real money for $160 billion in theoretical cost savings. We’ll come back to exploring why those cuts were so focused on areas of US soft power, and science - climate science in particular. For now, you can check out our chats with Professor Dana R. Fisher of American University where we discuss this at length.

Someone spotted - whether Musk or someone else and Musk agreed - that the “US Digital Service”, the pre-existing outfit re-branded as “DOGE”, was an ideal vehicle for carrying out what Carole Cadwalladr termed a “Digital Coup”. Putting aside the horror of the whole thing, the strategy was effective. Not in service of saving money, but of eviscerating a good chunk of the bureaucracy in just a few weeks, and gaining control of previously unaccessible data of the highest quality on Earth.

Time will tell whether DOGE (whatever the social, legal, constitutional, and economic cost) actually cuts spending.

What should come as no surprise, but inevitably has, is that the red thread tying together what we know so far of DOGE is access to data. The US government, at a conservative estimate, maintains exabytes of data (that is…a lot) that does not exist anywhere else and cannot be purchased at any price from a data broker. Medicare records on 25% of the US population, social security and IRS records of all income and tax returns of the whole US population, facial recognition and other biometric data for a major chunk of the population, NSA intercepts of digital communications, contracts, labour negotiations, etc. Edward Snowden was a cheap amateur punk with narrow horizons, in comparison.

As I was writing this, The Atlantic dropped a piece by Ian Bogost and Charlie Warzel - gesturing towards where all that might be going: “American Panopticon”, detailing how the previously siloed data on Americans could now, thanks to DOGE, be pooled to create a surveillance state to rival China’s. It builds on previous reporting from WIRED and others about the potential pooling of data to target undocumented immigrants in the US.

But what if any governmental use of data “exfiltrated” from these previously separate “data lakes” was a secondary objective?

Bogost and Warzel hint at what we’re driving at:

Musk has said that his goal with doge is to serve his country. He says he wants to “end the tyranny of bureaucracy.” But around Washington, people are asking one another what he really wants with all those data. Keys to the federal dataverse could, for example, be extremely useful to a highly ambitious man who is aggressively trying to win the AI race.

We already know that Musk’s people have access to large swaths of information from federal agencies—what we don’t know is what they’ve copied, exfiltrated, or otherwise taken with them. In theory, this material, whether usable together or not, could be recombined with other identifying information from private companies for all kinds of purposes. There has been speculation already that it could be fed into third-party large language models to train them or make the information more usable (Musk’s xAI has its own model, Grok); outside firms could use their own technologies to make sense of disparate sets of data, as well. Such approaches, the federal workers told us, could make it easier to turn previously obfuscated information, such as the individual elements of a tax return, into something to be mined.

Tech companies already collect as much information as possible not because they know exactly what it’s good for, but because they believe and assume—correctly—that it can provide value for them. They can and do use the data to target advertising, segment customers, perform customer-behavior analysis, carry out predictive analytics or forecasting, optimize resources or supply chains, assess security or fraud risk, make real-time business decisions and, these days, train AI models. The central concept of the so-called Big Data era is that data are an asset; they can be licensed, sold, and combined with other data for further use. In this sense, DOGE is the logical end point of the Big Data movement.

Coincidence or no, Musk’s xAI - a few days after absorbing the former Twitter into its structure, and weeks in to the DOGE operation accessing nearly all US government data - inked an agreement to vastly expand its “Colossus”14 supercomputing data centre in Memphis, Tennessee.

We cited this bit from the Isaacson bio in Part I:

He also realised that success in the field of artificial intelligence would come from having access to huge amounts of real-world data that the bots [sic] could learn from. One such gold mine he realised at the time was Tesla, which collected millions of frames of video each day of drivers handling different situations. ‘Probably Tesla will have more real world data than any other company in the world,’ he said. Another trove of data he would later come to realise was Twitter, which by 2023 was processing 500 million posts per day from humans.

Conclusion

You’ve done very well and thanks for sticking with us. So:

The world’s richest man, for more than a decade, has hinted he thinks an AI-dominated future is inevitable and has invested accordingly.

In the most generous version, he thinks that AI future could be ‘aligned’ (ala Banks’ Culture novels) with the best interests of humanity, but that unless extreme action is taken that won’t happen.

The same person invested to ensure the election of Donald Trump, and as his prize took a role that gave him access to all of the information possessed by the US government.

He then (reportedly) may have used the access to “exfiltrate” that data, which may be the most valuable data in all of history, if you wanted to “train” an AI large language model with first-party data on hundreds of millions of actual people that no one else could even buy.

And now for the scary bit: what if Musk’s is actually the “benign” scenario? Wait til you see what’s behind Door Number Two.

Abundance for All?

As Bastani wrote nearly a decade ago, the challenge of this moment is that present circumstances feel like they have outrun the ability of political/economic systems, and the philosophy upon which they rest, to cope.

This is not a new concern, but it would be silly to argue that the current moment does not feel like that is true.

That feeling is real. And it is driving actors of good or bad faith across the spectrum - some of whom are, as a result, willing to do some pretty extreme shit.

My challenge is that while Musk has proven a useful piñata for people opposed to what they think he stands for, insofar as there is any durability for his ideas, that rests on the idea that technology can enable “abundance for all” in ways that were previously undreamt of.

If anything, as Adam Tooze wrote in the New York Times, accounts of a benign “post-scarcity” future - left or liberal - may be victims of a publishing cycle that never imagined a present as bleak as now. And therefore seem out of step with where we may be going.

Both books have arrived at an awkward moment. [emphasis added] Even more than “Abundance,” a book that might well have set the agenda for a Kamala Harris presidency, “What’s Left” is painful to read. Not because it is poorly written, or wrongheaded, or inadequately researched — but because its rationalism and its futurism belong to an era, an epoch, a framing that is no longer ours. Of course we may still prefer to discuss bold and sensible solutions. We probably should. But we have to reckon with a present reality that is not just more dangerous, but heading in a worse direction.

In Part III, we will explore what the Thiel-verse has to offer as a vision of the future that is in contention.

We may live to regret demonising Elon and his “abundance for all” agenda - sincere or not. What comes next may be the stuff of nightmares.

If your strong desire is to make me say “for whom?”, then I swear to Christ you are in the wrong parish, friendo. You are welcome to stay, of course. You are also welcome to STFU for a while.

VERY loosely linked to the real-world story that electrified public transit (‘streetcar’) systems in several US cities were bought up and dismantled in the 1930s/40s by a cabal of car, tyre, oil, and road-building companies to move to ICE buses, in order to ensure lock-in to combustion-engine vehicles. The court record is mixed, but what’s not in dispute is that some seriously shady shit went down.

We could go on, with honourable mention to endless iterations of “solar punk” that kept alive the dream of limitless, abundant, nearly free, electricity despite decades of all The Smart People™ saying “that’s ridiculous”. And no, it doesn’t matter whether you think these developments are good or bad. What matters for our purpose is whether knowing the stories and the ideas they contain are useful in predicting what their richest fans do next.

And…’wheeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!’ …damn it feels good to be a gangster.

Around 1930, Keynes wrote an essay suggesting that by 2030 Britain and similar countries could be living in a post-scarcity society. People might work, about 15 hours a week, but only to give meaning to their existence. But despite hundreds of “where’s my jetpack” style snark, Keynes was clear what conditions beyond mere technological possibility needed to exist in order to bring about what he saw as “possible.”

Paul Mason at IPPR wrote this diagnosis of why that possibility was not realised:

Keynes imagined a future where rising wealth led to falling inequality. Instead, economic wealth has grown slower than he imagined, while physical wealth and information wealth have grown faster and begun to detach themselves from the value system. I think the moment is coming where we have to recognise this and ask what it would mean to redesign society just as radically as Keynes’ generation did in the mid-1940s. The opportunity is to structure the economy in a way that the non-economic takes over from the economic; where art and life merge, and where – as the Scottish writer Pat Kane puts it – the play ethic takes over from the work ethic.

No shade on how Stephenson makes his money - I’ve certainly consulted with some ‘controversial’ characters in some ‘controversial’ places around the world, some of whom were definitely billionaires or on their way to becoming one.

Too many pixels have been spilled on whether any of these philosophers were “existentialist”, because the term didn’t exist when they wrote, to detain us here. But “existential”?

Isaacson, Elon Musk, p. 30

If Musk ever launches a transhumanist startup offering to install/grow glands in people that allow them, with just a thought, to secrete chemicals with effects similar to ketamine, or MDMA, or THC, or cocaine, etc - that might work as an explanation. The Culture folk do know how to have a good time.

No word if, like Ontario’s decision to cancel a Starlink contract, there is so far any blowback in Canada to the Neuralink trial because of its association with Musk.

Whether this Detroit big muscle-car, energy-intense approach to developing AI via brute force was the only way has been challenged by China’s DeepSeek, which in some iteration can apparently run on little more than a Raspberry Pi. The potential that all of that investment in brute force compute might not have been necessary roiled tech and energy stocks for weeks - Trump’s tariffs then dramatically changed the subject and pushed that narrative into the background. But for investors and technologists with attention spans longer than squirrel-chasing dogs it’s a debate it’s certainly not going away. But we digress. Which is why it’s in a footnote. Are you still here?

Isaacson, Elon Musk, p 379

I’m sure it seemed like a good idea at the time, was done soberly for art’s sake, and without the influence of any chemicals on the decision to burn a million GBP in cash.

The 1970 film. Basically, 1982’s ‘WarGames’ with more rumpy-pumpy, wherein a supercomputer becomes self-aware and…bad stuff happens. Deciding to name your supercomputer that is…a choice.